Itinerary

Necropolis of the Caves

Introduction

Welcome to the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Populonia. Populonia was the only Etruscan city to be built on the coast, a location that contributed to the development of the port and made it a strategic Mediterranean crossroads, a place of commerce and maritime traffic, and an almost obligatory stopover for all ships travelling in the Mediterranean Sea. Ancient Populonia was located in a strategic position on one of the most popular trade routes in antiquity. The town was divided into two distinct nuclei: the upper part – the acropolis, i.e. the heart of the ancient town with its public and religious buildings, and the lower part, which was centred around the port and the industrial district, where metals were produced: copper from the Campigliese mines and iron from the island of Elba. Iron working began in Populonia during the mid-6th century BC. Previously, hematite (iron oxide) had been worked on the island of Elba, so much smoke being released from its iron furnaces that, unsurprisingly, it was known as "la fumosa” (the smoky place). In the end, however, the Etruscans exhausted all of its resources needed to produce fuel, the island eventually being totally deforested. Thus, since it was no longer possible to produce iron in situ anymore, once the iron ore had been extracted from Elba, it was loaded onto ships and transported to the Gulf of Baratti, which was still densely wooded and where there was also coal to fire the iron furnaces. Over time, however, heaps of ferrous slag (leftover fused waste from the iron making process) piled up on the land surrounding the gulf, and even the ancient Etruscan necropolis of San Cerbone. The poorer social classes were buried in the piles of slag, while the aristocratic classes of the 4th-3rd century BC chose to reuse the old abandoned limestone quarries as a new burial area. Underground tombs were created by digging into the ancient quarry face, thus giving rise to the Necropolis of the Caves. Marked by red signs, the Cave Trail starts at the visitor centre, just beyond the Experimental Archaeology Centre at the entrance to the wood.

The Tomb of the Promotes and the Small Quarry

Three underground tombs, which were used from the 4th to the 2nd century BC, line the side of the quarry. The dromoses (access corridors) are dug into the panchina limestone quarry face and lead to the burial chambers. Unfortunately, when they were discovered they had already been looted and, nowadays, access is strictly forbidden. In one of them, there is a curious decoration – the face of a woman, a protome, carved into the rock panel facing the 3 tombs. A rough female head that an unknown sculptor was unable to finish, it is the only sculpture to have been found in the tombs of Populonia. These hypogea (underground tombs) belonged to families, and were used to bury several members of the same family. However, the tombs were carefully hidden: the entrances were sealed with limestone blocks, and the dromos was filled with earth and stones – probably to protect the chamber containing the riches of the deceased from looting, which has taken place throughout antiquity. Therefore, for each new burial that took place, the family had to empty the dromos, open the blocked up doorway, deposit the deceased inside the burial chamber, and then close up the tomb behind them on leaving. To the right of the tombs, traces of Etruscan excavation work and signs of wind and water erosion are clearly visible in the semi-circular limestone wall. Note the layers of sand that were deposited and cemented over time in the sedimentary limestone rock.

The scenic viewing point

From the belvedere, there is a breath-taking view: the panchina limestone wall with its excavated tombs in the foreground, with the coastal town of San Vincenzo beyond the beautiful Gulf of Baratti to the north, Campiglia Marittima, Suvereto and Val di Cornia to the north-east, and, in the distance to the south-east, the Gulf of Follonica. Can you see the big white limestone quarries to the north-east? That is Campiglia Marittima, where people have been extracting copper ore and argentiferous lead (silver-lead ore) since ancient times.

The Meeting Point

The archaeological excavations of the Necropolis of the Caves took place in two phases: the first dig was carried out in the late-1970s, a period in which the painted tombs were discovered. The excavation work resumed in 1997 and lasted until May 1998, the period in which the area you can admire in front of you was discovered. The Necropolis of the Caves archaeological site has been open to the public since July 1998. This site was frequented by the Etruscans in two different periods: first, from the 7th to the 5th century BC, when this area was a quarry from which the Etruscans extracted blocks of limestone, also called "Panchina Calcarenite", a sedimentary rock formed on the seabed used as a building material. In fact, the tombs of the necropolis of San Cerbone were built with this stone, and its use as a building material continued, not only in funerary architecture, but also in the construction of the walls and buildings of the town of Populonia. Blocks of Calcarenite, along with stones and slabs of other types of rock, were also used to build the monuments of the Roman acropolis, the panchina limestone being mined in the quarry prior to the creation of the Necropolis of the Caves, and in the Buca delle Fate (“Fairy Hole”) area. Subsequently, when San Cerbone and Casòne were abandoned as burial areas in favour of iron and steel production in the 4th century BC, this area became a necropolis. The Etruscans dug their tombs in the ancient, now abandoned quarries, carving chambers into the rock in which to bury their dead. These underground tombs have a quadrangular burial chamber, with three funeral beds carved into the rock for the deposition of the deceased.

The Quarry

The quarry was abandoned when it was still being mined, the presence of carved blocks ready for extraction bearing witness to the sudden withdrawal of activity from the area. It is not exactly clear when or why the quarry was abandoned and the tools used by the quarrymen have never been found by archaeologists. However, during the excavation of 1997-8, numerous traces of tool marks on the rock faces were found, the study of which pointing to the type of tools that were used in the quarry, including: pickaxes, wedges and chisels – fine point chisels and broad point chisels. To extract the blocks, the Etruscans used a pickaxe to dig a groove around the block to be extracted for carving. Then, with the use of wedges placed at the base of the block, they levered it in order to detach the block from the quarry bed. Since limestone is a sedimentary rock made up of layers of grains of sand that deposited and cemented over time, they followed the stratification of the rock when extracting the blocks. In this way, the block detached form the quarry bed easily without breaking. Note that the curve of the quarry face follows the stratification of the rock. Once the blocks were extracted, they were lifted using a winch system and loaded onto wagons to be transported to the construction sites for working. Before the archaeological excavation took place, this area was completely covered by a layer of material made up of pieces of panchina limestone mixed with earth, which came about directly as a result of the mining activity carried out at the quarry. This layer of earth and stones has only been partially excavated, however, from the drilling of boreholes next to the quarry, we know that it was 5 metres deep, meaning that the actual quarry must be much deeper. Indeed, in front of the necropolis, the layer of stones and earth is 8 meters deep, so there is still a lot to excavate! Looking up and down the quarry face, it is clear that the quarry continues in both directions albeit covered by vegetation. Thus, what we can see here is only a small part of the Etruscan quarry face that extends for hundreds of meters into the woods.

The Tombs of the Quarry

Seven pit tombs and three sarcophagus tombs were discovered buried under the layer of residual mining material, a mixture of broken stones and earth, in front of the quarry. Only one of the sarcophagi is visible, most likely being a child’s tomb because of the type of grave goods it contained – astragali, animal bones used for play, a pastime similar to the game of dice, were found inside. In one of the pit tombs, on the other hand, the remains of a man who lived about 2,400 years ago and was around 40-45 years old when he died was found. He was about 1.65 meters tall and was well-built. His teeth were very worn, perhaps serving him during manual work as a third hand, and he ate mainly meat and few cereals. The man died of cancer, which originally affected his lungs before spreading to the bones of his torso and limbs, a disease almost certainly caused by the inhalation of fumes from the metal working activity carried out in the region.

The Necropolis

Looking at the rock face, you can immediately notice numerous chisel marks, which were probably used to smooth the surface. Each opening in the rock face corresponds to a chamber tomb, each chamber being enclosed by panchina limestone blocks and containing three funeral beds carved into the rock for the deposition of the deceased. Unfortunately, in the 1960s, these tombs were almost all looted. In fact, on the right, you can still see a part of the tunnel dug by grave robbers to reach the first level of the necropolis and access the burial chambers. Only so-called Tomb 14, which was lower down the rock face than the others, was saved from looting. There are also two Etruscan inscriptions, which have to be read from right to left, on the rock face. The first is located about one meter above the tomb located furthest to the right: the name ANAS, perhaps the tomb owner’s name, is inscribed on it. The second inscription is at the same height as the first but is located further to the left. Is it a small circle that seems to enclose the number 150, perhaps offering an insight into the use of the quarry by Etruscan workers? The vertical holes that you can see in the upper part of the rock face are natural cavities caused by erosion.

Tomb 14

Found intact during the excavations of May 1997 , Tomb 14 was still sealed by a series of panchina limestone slabs. In front of the entrance, traces of burnt wood, perhaps remains of the funeral pyre were found. The tomb consists of a quadrangular chamber, with three stone beds complete with stone cushions carved into the rock. Inside the chamber, the priceless grave goods of a cremated woman were found intact. On the funeral platform at the back of the chamber, the remains of burnt bones and a gold earring were found. On the bed on the right, there was a set of vessels for pouring and consuming wine: an amphora, two pitchers and four cups painted black, as well as the remains of two lead candlesticks that had partially fallen to the ground. On the bed on the left, there was a ceramic jug. These grave goods indicate that the deceased was probably devoted to Dionysus, the god of wine. The vessels used during the funeral were found on the ground: a small jug and a pàtera (dish) for the libation, plates, a cup and a small olla (earthenware pot) for food offerings, and an amphora (jug) containing water for purification. The grave goods from Tomb 14 are housed in the Archaeological Museum of the Populonia Territory in Piombino, where you can also see a reconstruction of the tomb, with its finds displayed exactly as they were found at the time of the excavation.

The dice – symbol of the Meeting Point

On the rock face to the left of tomb 14, you can see a sort of large dice, the symbol of the meeting points in the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Populonia, carved into the rock. It is still a mystery as to how it was possible to etch around the dice so precisely, not to mention how it would have been possible to extract it, if this had been the intention of the ancient quarrymen. A block designed and carved for the creation of an unfinished sculpture? The beginning of excavation work on a new chamber tomb, which was later considered too close to Tomb 14? This dice symbol seems destined to remain a mystery!

The Tomb of the Blacksmith

After visiting Tomb 14, go up the steps and turn right. On your left, you will find a niche carved into the rock face, inside which was found a strigil, a metal instrument used at ancient spas or gyms to scrape the body clean of the mixture of oil and powder which was applied to the skin in order to cleanse it. On the other hand, in front of the niche, a slag heap which had almost certainly been deposited on purpose was found, thus meaning that it was probably among the funeral possessions of a blacksmith.

The Painted Tombs

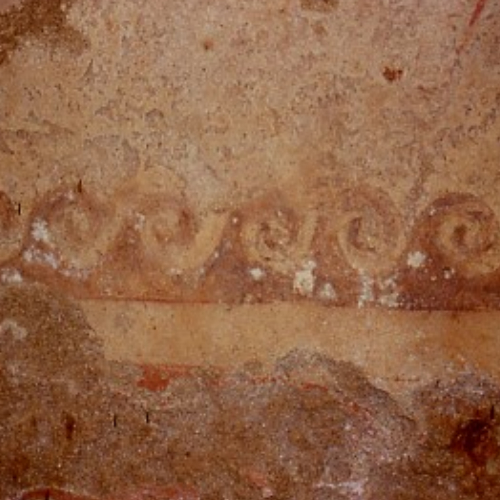

Continuing along Via delle Cave, the path which runs past the quarries, you will see a series of 9 aligned tombs which were excavated next to each other and found during the first archaeological dig in the late-1970s . They make up a large complex of underground tombs, with access steps carved into the rock. Before reaching the Painted Tombs, we pass in front of a tomb that was never completed. The workers only had time to carve the access steps to the chamber before the work was halted. The last two tombs are the only painted tombs to have been found in Populonia: the Tomb of the Dolphins and the Tomb of the Corridietro – the only tombs in the cave necropolis to have an arched entrance, all the others having a square-shaped entrance. These Painted Tombs have very simple frescoes: painted dolphins, which have all but faded away, on the door jambs, a ram's head at the base of the funeral platform, and a series of red waves on a yellowish background on the walls of the chamber. It is believed that the waves and the dolphins were in charge of transporting the soul of the deceased to the afterlife. Most of these tombs have been looted since the Roman age. In the access stairways, the remains of funerary statues, demons of death or ferocious animals, such as lions that had the task of guarding the tomb were found. The materials found indicate that the necropolis was used between the late-4th and early-2nd century BC.

Neighbouring Tombs

Continuing along Via delle Cave, the path which runs past the Painted Tombs, you will see some other tombs, some of which are in poor condition because they were partly destroyed by the subsequent quarrying of panchina limestone – a building material used for many centuries in Populonia. The excavation of one of these tombs has brought to light numerous objects found along its dromos (the entrance corridor leading to the chamber): plates, cups and jugs were piled up together, and food remains were found in a thick layer of ash – probably traces of the funeral banquet which had been consumed before the tomb’s entrance stairway was filled with stones and debris to seal it off definitively. The materials found indicate that the necropolis was used between the late-4th and early-2nd century BC.