Itinerary

Guided tour for adults

Introduction: Walking in the Palazzo Novo

Welcome to the Archaeological Museum of the Populonia Territory. We are currently in the area of the ancient Citadel of the Appiani, the family that ruled over the city between 1399 and 1628. In the square overlooking the entrance, it is still possible to admire the Chapel of Sant'Anna, an ancient church reserved for the lords and their Renaissance court, and the cistern for collecting rainwater, with the effigies of Jacopo Appiano III, his son, and his wife, Battistina. Unfortunately, the sculptures were defaced by the blind fury of Cesare Borgia's soldiers, who occupied the city of Piombino in 1502. Restored in 2001 as an exhibition venue, the museum is located inside the 'Palazzo Nuovo', which was built in 1814 and designed by the architect Ferdinando Gabrielli to house the court of the Princes of Piombino, Felice and Elisa Baciocchi, Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister. An integral part of the Val di Cornia park system, the museum is dedicated to the memory of Antonio Minto, the archaeologist who discovered many of the major finds of Etruscan Populonia, which are currently visible in the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Polulonia. The museum was founded to conserve and make accessible to the public the immense archaeological heritage discovered during decades of research, and to illustrate the long history of this territory from prehistory to the present day through the reconstruction of its environments and landscapes. The museum itinerary is divided chronologically into historical periods, from 500 thousand years ago to modern times. Each room contains a summary panel highlighting the most important characteristics of the historical period and detailed archaeological information, allowing you immerse yourself in the spirit and society of the period. At the bottom of the panels, there is also a timeline that will allow you to orientate yourself in history. The route begins in the rooms on the first floor, which are accessible either by taking the lift on your left, or by ascending the ancient staircase on your right. Enjoy your trip through Populonia’s history!

The Paleolithic hunters of Val di Cornia

The first traces of man in this area of Tuscany can be traced back 500,000 years to the Stone Age, i.e. the Lower Paleolithic. Mainly used for hunting, simple river pebbles in freshly worked jasper, with detachments on the two faces as a result of percussion, were found in a deposit located on an ancient sea beach in the Collinaia area, near Bibbona, in the hinterland of San Vincenzo and Massa Marittima, where tools with more advanced chipping techniques were also recovered. Despite their apparent simplicity, these tools were worked with a wisdom that demonstrates how our ancestors had the ability to predict the effect of repetitive blows on stone to create cutting edges, sharp edges and sharp points, a form of knowledge derived from the passing on of experience through the generations: culture. More recently, in the Middle Paleolithic, about 50,000 years ago – when Elba and Corsica were still connected to the mainland, the sea being much further away and the climate more humid – a Neanderthal settlement was found in the area of Botro ai Marmi, along the road that leads from San Vincenzo to Campiglia Marittima. As evidenced by the faunal remains, these Neanderthals survived by hunting wild animals, which they killed using expertly crafted flint and jasper tools including sharp points, scrapers and grinders. Early axes may have been used to cut tree branches. Homo Erectus appeared 20,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic, when the sea slowly began to creep between the mountains, covering the large expanses of the plains. During this period, there was a corresponding evolution in vegetation and animal species, accompanied by more archaeological evidence. Although traces of long-term, permanent settlements have not yet been identified: stone grinders, scrapers, blades, and pointed tips document the passage of temporary encampments of small groups of humans in the area between Alta Val di Cornia and the sea. Over the millennia, Paleolithic men and women began to question the nature that surrounded them, and perhaps even the afterlife. In fact, 15,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic, near a cave in Lustignano in the Alta Val di Cornia region, a hunter decided to engrave what he had seen with his own eyes on a pebble: a bison that had been pierced by arrows while trying to run away. Was it an amulet, or perhaps an expression of gratitude for a favourable hunting trip? Whatever its meaning, it is certainly an extraordinary example of Paleolithic art.

The Neolithic revolution

The introduction of agricultural practices is often only evidenced by the presence of ceramics. In fact, the use of cultivated grasses and vegetables gave way to clay containers which were used to preserve, cook and consume food, and pottery demonstrated that the diet of the time included foods other than meat. To the north of San Vincenzo, near the present-day Garden Club tourist village, archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a grain silo dug out of the sand dating to the early Neolithic period, almost 7,000 years ago. The finds that you can see on display in the showcases – fragments of ceramics for daily use, including flasks, vases, and bowls with simple decorations obtained by imprinting shells or pointed stone instruments – also come from this area, which was frequented at least until the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. Although no traces of housing structures have yet been found, the significant discovery of thousands of ceramic fragments in the Orti Bottagone Oasis, where a farming village probably existed for a long time, has been dated to a period between the 4th and 3rd millennium BC. This set of ceramic artefacts contains bowls, cups and large containers in coarse locally produced pottery, and undoubtedly makes up the most important source of archaeological research in this region of Tuscany.

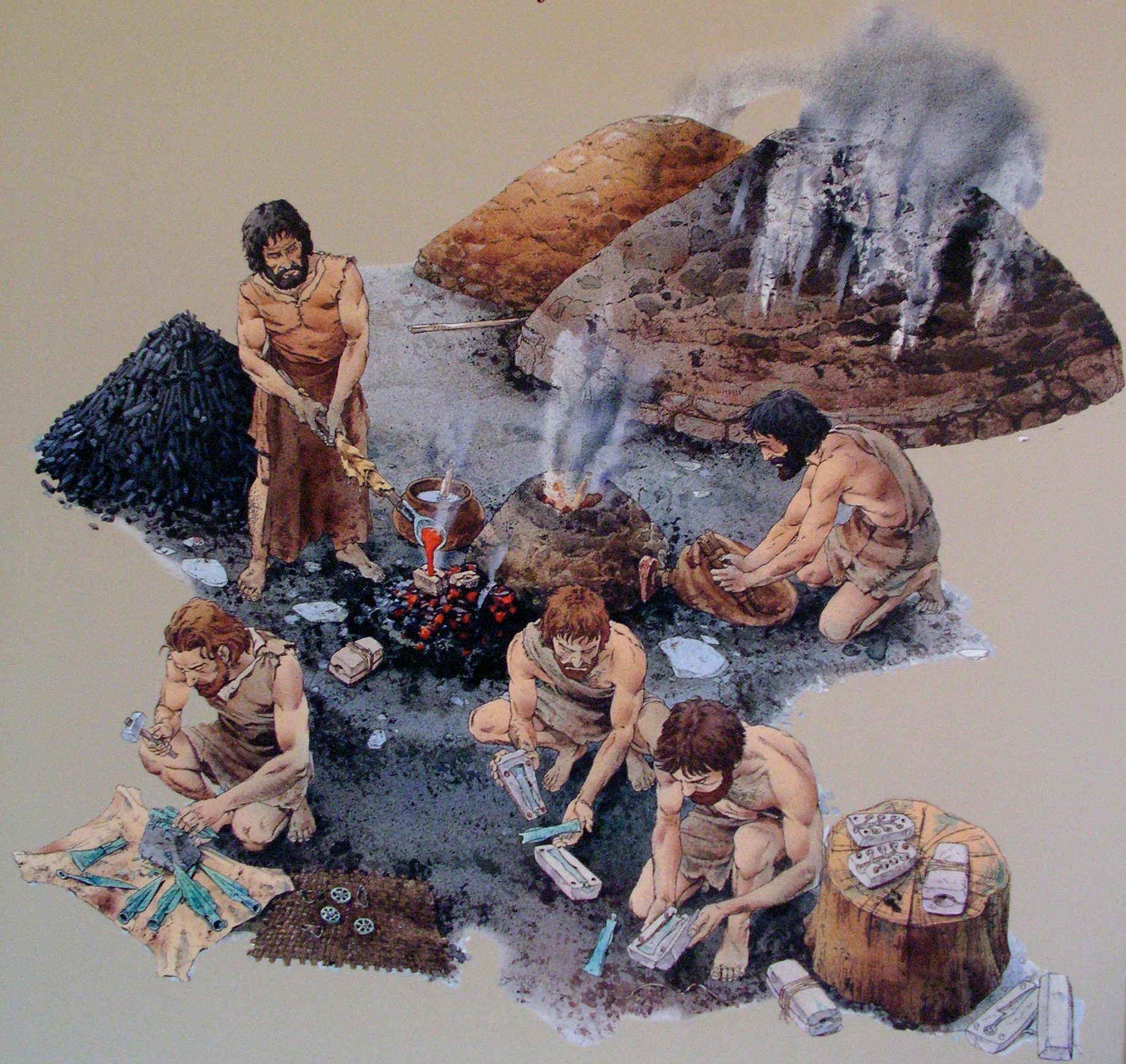

Metal working in the Campigliese Hills

Site of the present-day San Silvestro Archaeological Mining Park, the Campigliese Hills contain very rich in deposits of copper, lead, silver and tin. The availability of these metals made the early exploitation of copper ores possible, which lead to the production of durable objects, such as weapons and tools. In fact, in the area of the Solvay quarry, in the hinterland of the San Carlo hills, at least 3 furnaces located on copper slag heaps dating to the end of the 3rd millennium BC have been identified, suggesting their long usage. The ancient finds left by these early metal workers, who put an end to the Stone Age, are on display, including: ceramics, slag, stone pestles, crucibles and actual drops of molten copper, all significant indicators of extremely advanced technological capability for the time. Recent studies have shown that an axe belonging to Ötzi, a personality whose mummified remains dating back more than 5,000 years were found in glacial ice on the border between Italy and Austria, came from the mines of this area – a completely unexpected discovery since, until recently, it had always been assumed that it was made from Alpine copper. Radiocarbon dating of the wooden handle proves that artefact was made in this area between 3346 and 3011 BC, thus meaning that Val di Cornia’s Copper Age had already started as early as the second half of the 4th millennium BC. In the showcase, you can also observe a vase, most probably used at a burial, which was found in the locality of Gagno, on the outskirts of Piombino. The characteristic flask shape is typical of the Rinaldone culture, which was widespread in central-southern Tuscany – further evidence that the Populonia promontory was frequented in the Copper Age.

The storage rooms and villages of the Bronze Age

Populonia’s metal-working background is also reflected in the extraordinary nature of the finds in the area. 35 circular copper panels dating back to the 18th century BC, which were originally contained inside a large ceramic container, were found at Riva dei Cavalleggeri, in San Vincenzo. The function of these singular ingots is not clear, although the homogeneity of their shape and weight would suggest a sort of pre-monetary reference used during increasingly frequent commercial exchanges. Perhaps to facilitate the sale of valuable metal products, there was a marked increase in the number of settlements on the Populonia promontory between the 12th and 10th centuries BC, especially along the coast. The most famous village at the time was Poggio del Molino, on the northern side of the Gulf of Baratti, whose archaeological excavation has made it possible to reconstruct its daily life. Although the settlement's huts were built with perishable material, it was possible to reconstruct their shape by observing the arrangement of the post holes used to support the load-bearing structures. The panel shows you how the Bronze Age village of Poggio del Molino must have looked. Animal remains testify to the presence of dogs as domestic animals, the breeding of oxen, sheep, goats and pigs, the use of birds of prey for hunting, and document the importance of wild boar, fishing and shellfish for nutrition. Agricultural practices are indirectly evidenced by the presence of millstones and grinders, sometimes made of imported basalt stone. The community founded an area on the slopes of one of the hills which was used as a necropolis, where fifty globular or biconical urns, containing the cremated remains of the dead, covered with bowls and often embellished with geometric motifs, were found. Cremation was the sole burial rite of the time, the urns containing the burnt remains of the dead being placed inside a well.

The Iron Age: the Villanovan culture

Between the late-10th and 9th centuries BC, bronze Age settlements were abandoned in favour of inhabited areas located on the Gulf of Baratti and the slopes and summit of the hilly Populonia promontory. Knowledge of the actual nature and extent of these villages is still limited, but we can observe their characteristics from the study of the necropolises that extend over the plateaus and small hills. The first pit burials began to appear in the mid-9th century BC, the cremated ashes of the deceased being placed into biconical urns covered by bowls, and usually buried in a special well covered by stone slabs, like the one you can see in the reconstruction in this room. A clear social and gender distinction begins to emerge. Iron Age men and women wanted to ensure not only a worthy burial that reflected their rank, but also grave goods for use in the afterlife – bronze weapons for men, and spears, spools and spindles for women. Both sexes, however, were buried with objects of personal ornamentation, such as pendants, chains and fibulae (brooches or pins used to secure clothing). As you can see in the showcase, the grave goods found in Poggio delle Granate contain many objects produced outside the local area, including a Sardinian jug from Poggio delle Granate, with its characteristic spout shape. It is not clear whether these vases were imported as luxury objects for wealthy clients or as part of wedding trousseaus belonging to Sardinian women. What is certain, however, is that relations between the island of Sardinia and Populonia intensified in this period.

The Iron Age: the first family tombs

The first examples of chamber tombs appeared very early in the territory of Populonia, the first examples of collective tombs capable of hosting multiple members of the same family dating back to as early as the late-9th century BC. Here you see the reconstruction of a chamber tomb, which was excavated in the 1980s near the Gulf of Baratti. Built into the rock, the tomb already had all the typical characteristics of the Tumulus tombs of the Orientalizing age: a pseudo-dome vault and a central chamber to house the dead and their grave goods. The remains of two bodies, those of a young woman and an elderly man, were discovered. Unfortunately, however, as was often the case, grave robbers had looted the tomb, the only grave goods remaining including two bronze sewing needles, an amber necklace and knife handles – the theft of grave goods over the centuries depriving us of a substantial amount of information about the owners of the tomb and the society in which they lived. The grave goods of four rich burials from tombs dating between the late-9th to the mid-7th centuries BC were found in Poggio del Telegrafo, the area where the Acropolis of Populonia would soon be built, are also on display here. The objects chosen for the afterlife reflect the growing wealth of some members of the community, and include: brooches, hooks, spears, axes, and even razors. Certainly the most valuable objects of the burials that you can admire are the bronze cap helmets, and a wonderful belt decorated with embossed solar discs and bird heads, which were used to secure fine clothing.

The orientalizing age: the wealth of Etruscan princes

The room you have just entered only partially manages to demonstrate the astonishing wealth of the Etruscan princes who commissioned the imposing Tumulus tombs overlooking the Gulf of Baratti. The grave goods placed in these tombs between the late-8th and the early-6th century BC not only reflect the refined taste of these aristocracies, but also a trade network in which Populonia, the only Etruscan city on the sea, was fully involved. In fact, due to the huge amount of luxury items which were imported from Greece, Egypt, Phoenicia, Cyprus and Turkey during this period, this phase of Etruscan civilization is known as the 'orientalizing' age. This showcase houses the extraordinary set of vases found in the Tomb of the Fìttili, many of which are aryballoses, containers used to infuse olive oil with herbs, aromatic plants and flowers, such as irises, roses and lilies. Some of these vases were made in the Greek city of Corinth, one of the fashion capitals of the time, the use of crimson clay and banded decorations clear evidence of their Corinthian origin, and underlining how elegant and in vogue the owners must have been. The others, on the other hand, were made in Etruria, inspired by decorative Greek models, perhaps using local fragrances and oil. Another unusual artefact belonging to the grave goods of the same tomb is a curious balsamarium of Greek-Oriental production in the shape of a duckling, which contained ointments and an ear cleaner – a cotton swab more than two thousand six hundred years old!

The tomb of the Populonia goldsmiths

The Tumulus tomb of the goldsmiths in Baratti yielded very rich and varied grave goods, dating to between 640 and 550BC. The family of the deceased and owners of the tomb chose to use a very refined set of pottery during the funeral banquet, which was then left inside the tomb for the deceased to use in the afterlife. Along with the usual and colourful pottery of Greek (or imitation Greek) origin, with painted bands and decorations, there are many vases with an unusual black colour called bucchero – the typical Etruscan ceramic, which was immediately recognizable and mainly used to make vessels for drinking wine and water, and some types of crockery. Because of its high production cost, few people could afford to produce this type of ware, which, after being dried in the air, was fired in ovens devoid of oxygen, thus triggering a series of chemical reactions which caused the typical black colour. The grave goods also included a tripod of Phoenician origin, which was used as a mortar to grind spices, and a quite unique object called a 'graffione', which could have either been used as a skewer for succulent morsels of meat or as a torch holder. The ladies buried in the goldsmith’s tomb wanted to bring splendid jewels with them on their journey to the afterlife, the artefacts found demonstrating the great skill of Etruscan master gold workers in the 6th century BC, who put into use artistic and technical secrets learned from the Near East. The pair of earrings decorated with rosettes and the two acorn-shaped clasps that you can see on display here are masterpieces which highlight the techniques of granulation and dusting and, if you look closely, you will see that the gold leaf surface is covered with tiny gold spheres which are often so small in size that they look like dust. In fact, the techniques of granulation, dusting and watermarking are still used today in order to create unique jewellery.

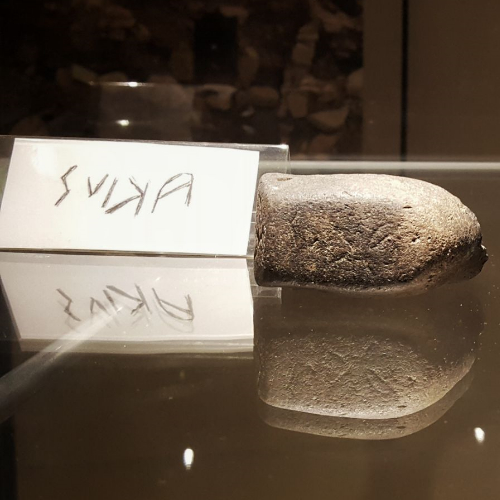

Local miners and metals

As previously mentioned, the Campigliese Hills contain vast deposits of strategic metals such as copper, lead and silver, the exploitation of which began in very ancient times. In fact, in the San Silvestro Archaeomineral Park, it is possible to see the entrances of the ancient mine shafts which were dug into the rock by Etruscan miners in order to reach the underground ore veins. In some very rare cases, we even know some of the miners’ names: the two oil lamps you can see on display here come from Val Fucinaia, one of them with a name on it: AKIUS, probably a miner who lived in Etruria in the 5th century BC, whose name was also found in Marzabotto. The shape of the lamps was basic and not graceful, but allowed the wick to burn the fuel it contained, usually olive oil. The two holes at the mouth of the other lamp allowed it to be fixed to a support so that the miner could keep his hands free to work. Dated to the 4th century BC, the two enigmatic sets of weapons and metal artefacts from Baratti beach further highlight the remarkable expertise of metal workers in this period. Initially interpreted as accumulations of objects to be melted down in furnaces and reused, their presence was later found to be connected with sacred altars found nearby. In fact, this find of ancient grave goods includes javelins, swords and their sheaths, spear tips and even a skewer. Despite being a recent find, archaeologists are already researching the origin of the weapons, some of which could be Etruscan, others of Celtic origin, probably trophies won in battle and dedicated to an unknown war deity.

Iron: the wealth of Populonia

The Gulf of Baratti is famous for the pristine beauty of its landscape. The Etruscans of Populonia, however, certainly wouldn't have thought so – the production of iron, obtained from the hematite (iron ore) which was imported from the nearby island of Elba, having had significant repercussions on the local environment and the beauty of the area surrounding the gulf. Elba had been deforested and stripped of its natural coal reserves before the 6th century BC, meaning that the hematite ore, which was mined on the island, could no longer be worked there. Thus, to meet the iron industry’s massive demand for coal, from the 6th century BC onwards, the ore was shipped from the island of Elba to the mainland, where it was crushed and burnt in furnaces, the reconstruction of one of which you can see here. Indeed, Populonia had a thriving iron working industrial district, which made it an urban centre of primary importance. Despite Populonia’s iron industry reaching its peak in the 4th century BC, the production of semi-finished iron products continued to play a dominant role during the period following the Roman conquest of the town in the 3rd century BC, locally-produced iron even supplying Scipio Africanus’s fleet during the second Punic war in 205 BC. However, this large-scale production of proto-industrial iron quickly led to the accumulation of vast amounts of fused waste, called slag, which ended up completely burying the Orientalizing necropolises of San Cerbone and Casone.

Wine, food, and music - Dining with the Etruscans

The reconstruction on display before you recreates the scene that guests at Etruscan banquets must have seen. The philosopher and historian Posidonius describes them thus: "The Etruscans have sumptuous tables set twice a day, colourful carpets and silvery cups of all kinds spread out, and are served by a crowd of beautiful slaves dressed in luxurious clothes". Indeed, the fame of Etruscan banquets preceded them. Lying in pairs on comfortable beds, guests conversed amiably with each other and listened to music played by specially hired professional musicians. Meanwhile, the servants efficiently served rich foods on elegantly decorated plates and poured rivers of wine into the diners' glasses. Recipes varied from season to season, above all depending on the opulence of the house owner. Delicious dishes of boiled or roasted meat, sourced both from farm animals (sheep and pigs) and game (roe deer and hare), were a regular fixture on the Etruscan menu, along with spelt, which was prepared in a variety of ways, from mixing it with other cereals in soups to unleavened focaccia, and puls, a sort of polenta. Could it be a coincidence that, still today, Tuscan menus heavily feature cereal and legume soups? Eggs and cheeses completed the meal, along with many different kinds of fruit including figs, plums, pomegranates, pears, and nuts such as hazelnuts, walnuts and chestnuts. Etruscan banquets were not simple dinners with friends, however. Food, wine, and company were often just the backdrop for gatherings needed to make difficult political decisions or seal alliances, as well as to celebrate religious festivals.

Populonia in the 6th and 5th centuries BC - The maximum splendour of the city

Despite the fact that archaeological research has made great strides, it has not yet managed to define with certainty the exact location and extent of Populonia between the 6th and 5th centuries BC. However, recent excavations carried out at the Necropolis of Casone and other cemeteries of the period have revealed the advent of new burial forms (such as Aedicule and Cassone tombs), the great wealth of the accompanying grave goods reflecting a phase of relative prosperity. In addition to the production of iron, the mint, the production of local ceramics and, above all, the creation of works in bronze also flourished in the city during this period. Found in a late-6th century BC funerary context, the wonderful horse rattle embellished the harness of the elegant steed of a lucky aristocrat from Populonia during the most important ceremonies. Imagine the mesmerizing noise this rattle would have made as the horse moved. In fact, for the Etruscans, the tinkling of bells was a way to ward off bad luck. As can be seen from the exhibits on display in this room, the opulence of the Populonia territory in the 5th century BC is also revealed by the presence of astonishing vases imported from Greece. Corinthian pottery was no longer the only ware to attract the Etruscan market, and was even surpassed in quality and quantity by ceramics from Athens, including the large krater decorated with a banquet scene, the long-necked ointment vase (lékythos), decorated with an elegant female figure and a swan, and the pelìke decorated with the fight between Theseus and the Minotaur. The pelìke was a vessel usually used as a container for liquids, but the one that was found in the necropolis of Casone in Baratti contained ashes from a child’s burial.

Flying with Triptolemus

In 1955, an elongated pit containing an Etruscan chariot, the skeletons of two horses, and the metal elements of their harnesses was found inside the Necropolis of San Cerbone. The pit was first interpreted as a religious offering since it did not appear to belong to any tomb. More than half a century after the discovery, however, a detailed study and reconstruction of the original site based on the evidence available led to a new theory: that the pit with the chariot was actually the underground chamber of a monumental mound, which was destroyed by modern iron ore waste recovery operations. Contrary to what scholars claimed only a few years ago, the vehicle is not a war chariot, but rather a celestial chariot – an indispensable vehicle for transporting the soul of the deceased to the afterlife. Reassembled and in their original location, the bronze decorations, depictions of bearded snakes, along with wings on the side, a common symbol of life after death, directly point to immortality in the afterlife. Indeed, ancient mythological tales tell of Triptolemus who, under the protection of the goddess Demeter, used his winged chariot to teach agriculture to the Greeks. The end of the reins is crowned by the head of a young ram with large almond-shaped eyes, which must have been filled with gems. While the bronze parts were already part of the Piombino Museum collection, the iron elements had always been kept in the deposits of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence where, unfortunately, they were damaged by the 1966 flood. In fact, if you examine the archive box housed in the Florentine Museum, you can still see the traces of dried mud – evidence of that terrible tragedy.

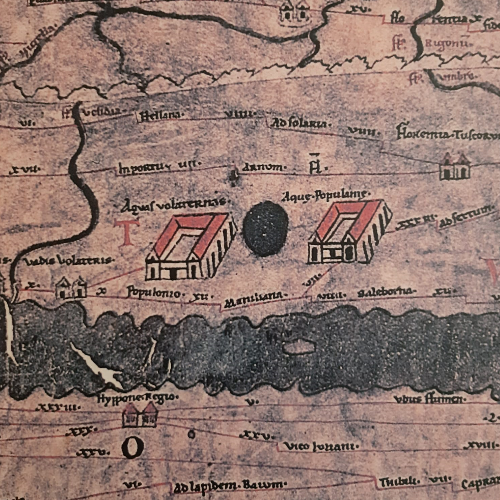

The metals and coins of Populonia’s mint

5th century BC Populonia had a very strategic geographical position, and was the hub of international trade routes that brought goods from all over the Mediterranean. Thanks to the rich metal ore deposits in the Campigliese area, Populonia began to mint coins very early compared to other Etruscan cities, the first public issue silver coin featuring the Chimera monster on one side and no image on the back dating back to the mid-5th century BC. The aureus (gold coin), which was minted with a lion's head, dates back to a similar period. The series of silver coins featuring the monstrous Gorgon – the famous Medusa, who had snakes for hair and is connected with the legend of the city’s ancient name, POPLUNA – as well as those minted with the bust of Athena and the head of Heracles on them, belong to a second series. Made of bronze and having a strong connection with Roman coins and the Roman weight system, the last issue minted in Populonia dates back to the 3rd century BC, including: the coin with the head of Hermes on one face, and his typical winged staff with snakes on it on the other; the one with the helmeted head of Athena on one side, and her sacred animal, the owl, on the back; and the one with the head of Heracles on it, with his club on the flipside, all with the legend “POPLUNA” on them. The highly evocative series with the head of Hephaestus minted on one side, and a pair of pincers and a hammer on the reverse, was a clear reference to the patron god of Populonia and one of the town’s main trades – ironworking. Due to the suffocating political pressure of Rome, Populonia’s Etruscan mint closed in the late-3rd century, however its coins continued to circulate in the pockets of citizens until the early-1st century BC.

The finds of the Aedicule tomb – the bronze Offeror

The Aedicule tombs of the Necropolis of San Cerbone, in the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Populonia, were built as early as the 6th century BC. As you can see from the model of one such tomb on display here, its shape resembles a small temple, however they were in fact probably used as graves. The Aedicule of the bronze offeror was built in a strategic position at the crossroads of the two main roads of the Necropolis, the finds from its 1957 excavation being heterogeneous and covering more than two centuries of use. The most interesting find from the tomb is certainly the small bronze statuette, used to crown a candelabrum. At first, the small bronze was mistakenly believed to be making an offering to a deity. However, due to the statuette’s naked body and disc-shaped plate in hand, archaeologists now believe him to be an ancient athlete – a discus thrower. The name offeror has stuck, however! The grave goods found in the Aedicule tomb include beautifully worked gold and silver clasps and brooches, an ionic ceramic goblet, a bucchero ladle and an extremely unusual engraved carnelian, perhaps the bezel of a very precious ring. Despite the small size of the stone, the scene is extremely detailed, depicting Hercules (as stated in the Etruscan caption) killing Antaeus, a giant who was given invincibility by his mother Gaea (in which he regained his strength every time he touched the earth) by lifting him off the ground.

An Etruscan wine service

The grave goods on display in front of you offer a glimpse into the best of what was available on the Mediterranean market between the 6th and 4th centuries BC – nowadays what might be called ‘the essentials’ for the consumption of wine. An entire service made up of different materials, the presence of these objects inside the tombs of Populonia had a special celebratory function: they reminded those present at the funeral of the deceased person, who had hosted the sumptuous banquet so that their guests could cement their social ties. The favourite drink of princes, Etruscan wine was very different from today, however. It was very viscous with a high alcohol content so, in order not to appear barbarian, it was mixed with several parts of water and infused with fruit, honey and spices in a large two-handled container called a krater, and therefore needed to be filtered using sieves. There were certainly general indications on the doses to follow, but in the end it was the symposiarch - i.e. the man who managed the phases of the banquet - who decreed the quotas. Imagine the scene: the servant enters the room carrying two large containers, the krater of the symposium and the metal stàmnos. Using the ladle, called a simpulum, he draws water to mix with the wine according to the given prescriptions and adds, depending on the quality of the mix, honey, aromatic herbs, and even a touch of cheese. He then filters the precious mixture into jugs, called pelìkai and oinochòai, with a bronze strainer. The final, most pleasant act was the libation using the refined chalice, the kylix. Being a servant was certainly not an easy task!

Hellenistic Populonia and the Necropolis of the Caves

Populonia continued to prosper uninterruptedly thanks to the working of Elba iron and its strategic position on the Tyrrhenian trade routes. Between the 4th and 3rd century BC, the city had thousands of inhabitants and was one of the largest cities on the Italian peninsula. The excavations of the Necropolis of the Caves in 1997 confirm this great phase of prosperity, revealing the existence of an extraordinary series of chamber tombs obtained from an ancient local calcarenite quarry and dozens of other pits. Unfortunately, as so often was the case, most of the tombs had been looted. To great surprise, however, so-called Tomb 14, of which you can see the full-scale reconstruction here, was found still sealed. Despite having the appearance of the other family tombs that housed multiple burials, on the central platform inside Tomb 14, archaeologists found the cremated remains of a single young woman with a hoop earring lying on the ashes. The grave goods consisted of furnishings used for the girl's funeral, as well as pottery for the banquet: an amphora for sacred washing, a patèra, plates for food offerings, cups, and two lead candlesticks. The object that has aroused the most interest among scholars is perhaps the least conspicuous: on the left platform, isolated from the rest of the equipment, as if to give it relief, an achromatic jug called làgynos . It denotes that the deceased must have been a devotee of the cult of Dionysus, which included the use of very large amounts of wine during the ceremonies dedicated to him. You can now watch the video of the discovery of the intact tomb and relive the excitement of the archaeologists who excavated it.

Treasures and Ancient Shipwrecks

Between the 3rd and 1st century BC, Populonia and its territory were at the hub of a dense network of trade routes. From north to south, thousands of cargo ships sailed the seas to exchange valuable goods and respond to the increasingly demanding market. In the waters of Pozzino, near the Gulf of Baratti, underwater archaeologists have partially brought to light the cargo of a wreck sunk between 140 and 120 BC. The goods recovered from this ill-fated ship include dozens of wine amphorae from the island of Rhodes and Campania, glass made in the Syro-Palestinian area, Athenian pottery, Cypriot jugs, oil lamps from Asia Minor, and imported tinware probably from Campania. The cargo ship might have begun its voyage from the Palestinian coast bound for Cyprus, then stopped in Dèlos, an important Aegean port, where it picked up Greek goods before finally reaching the Italian coast. However, considering the quantity of goods produced in Campania, it cannot be excluded that the ship loaded all the goods in Pozzuoli, another ancient trade hub where goods from all over the Mediterranean converged. The presence of lead ingots on board would suggest that the ship sank after stopping at the port of Populonia, the precious metal having been mined in the hinterland. The excavation has even made it possible to recover interesting items belonging to the crew: a plumb-line (a depth-finder to probe the depth of the sea from the surface to the seabed), the hand of a religious statuette sailors worshipped, a table service, and even food remains such as walnut shells. Here you can also admire the remains of the ship's planking, perfectly preserved thanks to the protective action of the Neptune Grass (Posidonia Oceanica, a species of sea grass) rooted to the sea bed.

The luggage of a doctor

Rich aristocrats would not necessarily have owned personal ships, thus they would have to have loaded cargo to be able to reach their destinations, boats providing a passenger service to their customers. Archaeologists have discovered that there was a doctor on board the ship that sunk in Cala del Pozzino. Surprisingly, an iron surgical instrument and a bronze suction cup (called cucurbitula, or "small pumpkin" because of its strange shape) were recovered. Roman doctors would have heated its bronze edges and applied it to the painful parts of the patient, similar to the modern form of treatment called ‘cupping’. In the most serious cases, the suction cup was also used to perform bloodletting, which is not surprising as the Romans firmly believed that some evils could be "sucked" out of the body, thus eliminating harmful conditions. Also belonging to the doctor's luggage were 136 wooden vials in large cylindrical boxes, inside which were sealed, flat grey disks which, once analysed, revealed the presence of zinc compounds, animal fat, resin and vegetable oil: the exact recipe that Pliny the Elder had quoted as a cure-all for the treatment of eye infections. Eye drops more than two thousand years old!

The Arrival of Rome in the Populonia territory

In the 3rd century BC, Populonia was absorbed by the Roman Republic. Unfortunately, there is no documentation by ancient historians about this event, so it is not exactly clear how this passage of control took place: whether it was simply a passage of power or a real military conquest. Archaeological research is still on-going and could soon reveal the truth. The existing archaeological evidence, however, shows that Populonia had a leading role in providing Scipio's Roman army with the iron needed to defeat Carthage during the Second Punic War. Between the 3rd and 1st century BC, Populonia was a productive and refined economic centre. Temples, roads, baths and domuses (houses) were built on the Acropolis, the highest point of the city, and the houses of wealthy citizens and public spaces were embellished with columns, plasterwork and precious floors. In this room, you can admire two of the most beautiful mosaics found on the Acropolis dated between the late-2nd and 1st centuries BC. A masterpiece of Roman art, the mosaic’s motif is made up of perspective cubes that would certainly not look out of place in a modern art collection. The mosaic was found collapsed but almost intact in the foundations of the Loggia on the Acropolis, and would have decorated the floor the building, which was used as a belvedere. Through the skilful use of local rocks such as marble, limestone, jasper and painted terracotta (for the red band), the craftsmen managed to create the illusion of perspective, just like Escher! Found by chance in 1842 inside one of the two twin exedras near the recently excavated public baths in the area above the Loggias, the mosaic depicting the seabed, on the other hand, has a much more colourful history. Unfortunately, the beautiful floor decoration, which is made up of molluscs, crustaceans and fish, underwent several changes of ownership involving the mosaic being moved from one location to another. During one of these numerous transfers, it was involved in a road accident and fragmented into several pieces. It was therefore subsequently reassembled with some of the original pieces in their original position, some of them in random positions, and some pieces being reconstructed. Eventually, when it was put up for sale at a famous London auction house in 1995, this ancient “puzzle" was bought by the Italian state and restored to its rightful home. In the lower portion of the mosaic, which is certainly original, it is clear to see why an anonymous patron financed its difficult construction more than two thousand years ago. Visible only by observing the mosaic upside down , one can see a boat with three people on board which is being overwhelmed by a gigantic wave. The right way up, however, the white shell becomes a dove and seems to fly over the boat in difficulty. Archaeologists maintain that the mosaic could have been commissioned as a votive offering to the goddess Venus, the patroness of navigation, as symbolized by her sacred animal, the dove.

The abandonment of Populonia in the imperial age – the treasure of Rimigliano

In Roman times, the opulence of the town of Populonia was short-lived, the town being almost completely abandoned with the arrival of the first emperors. Reliable historical evidence from the famous geographer, Strabo, outlines the desolation and abandonment of the Acropolis beginning in the early-1st century AD: “with the exception of the temples and a few buildings, it is nothing but a small, completely abandoned centre”. Archaeological research has confirmed Strabo's description of the main settlement, but has also demonstrated the development of villas and settlements located both on the coast and distributed along the main roads from the Augustan age. In fact, in the 1st century AD, a farm was built in Poggio del Molino, to the north of the Gulf of Baratti, for the production of garum (a precious fish sauce), which was then totally renovated and turned into an elite seaside villa in the 2nd century AD. Furthermore, in the late Republican era, important buildings sprang up along the Via Aemilia Scauri, the main road in Vignale, including an agricultural villa which offered hospitality to travellers. Archaeologists have traced the loss of the Rimigliano treasure, a concretionary hoard of about 3,600 coins found by chance by a bather on the beaches of San Vincenzo, to this period. In order not to lose the original conformation of the coins, which were divided into little piles, only about 10% of the total was disassembled. Today, the treasure is kept in an aquarium which was especially designed to keep the treasure in perfect condition. The coins are mainly Antoniane, silver coins introduced by the Roman emperor Caracalla, the most recent issues being minted during the reign of Gallienus between 259 and 268 AD. It is not certain who the Rimigliano treasure belonged to. It could have been a collection of money intended for the legionaries stationed in Gaul in the third century AD, but it is more probable that it belonged to an unfortunate, rich merchant, whose ship sank off the coast of Rimigliano.

A stroll through the Mediterranean: the circulation of goods in the imperial era

Hundreds of transport containers from the depths of the Gulf of Baratti testify to the importance of trade in Roman times and the vitality of the Populonia port. In fact, even if he underlines the substantial decline of the city in the imperial era, the geographer Strabone, confirms that the port remained teeming with activity. A rather common find, the amphora actually contains a world of information and archaeologists have studied its shape and diffusion in order to decrypt the complex trade routes of the time. For example, we thus discover that wine from Tyrrhenian Italy was transported by Greco-Italic amphorae between the 3rd and 2nd century BC: Dressel 1 in the 1st century BC, and the one that it was replaced by in the 1st century AD: Dressel 2/4. Containers from Spain (Beltran I and II B) which contained gàrum, a much-loved fish sauce fermented in the sun, were widespread. There were also containers from Africa used for the trade of olive oil from the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. Once filled with their contents, the containers were closed in various ways. Terracotta discs often ensured the hermetic closure of oil amphorae, while wine amphorae usually had a cork stopper. Another closing system involved fitting an amphorisk, a small full vase, inside the neck. Much faster and cheaper than land transport, goods were mainly transported by sea, with amphorae always making up the majority of the load. The handles, called “lugs”, were used for a solid grip, the tip allowing them to be planted in the layer of sand that covered the bottom of the hold, and also to fit them in well aligned rows and maximize the load of the boats in the limited space available. There were even painted inscriptions, called tituli picti, usually on the neck and belly of the ampora, which indicated the type of goods contained, origin, weight and possible recipient – they were, in short, labels from thousands of years ago!

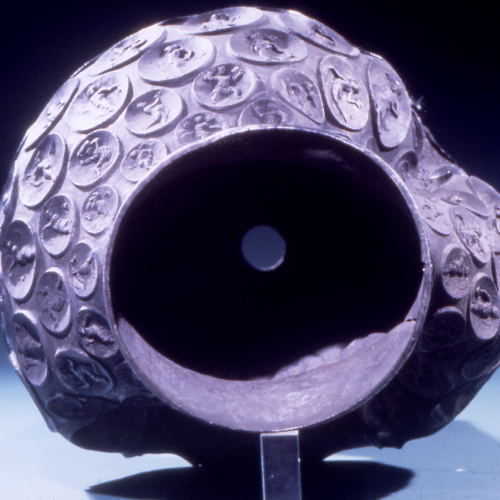

The Silver Amphora of Baratti - The story of a discovery

We have reached the symbolic masterpiece of the museum: the silver amphora of Baratti. Incredibly, the discovery of this extraordinary artefact was completely accidental. It was the spring of March 1968. The fisherman, Gaetano Graniero, was aboard his boat "La Bella Michelina" on the waters of the Gulf of Baratti, when he brought to the surface a strange object similar to a deformed bucket and covered with marine incrustations which was entangled in his nets. Not recognizing the value of the unusual rusty container straight away, his sailors gave it to someone who was more experienced and sensed easy money. Gaetano's wife, however, having heard what had happened, was determined to get the amphora back and bring it back home. Mrs Graniero, mother of nine children, later said: “Even though it was all dirty, I liked it and wanted to keep it in our house, so I put it under the cradle of our last born.” Neither Graniero’s wife nor his crew were aware of what the law stated, so they did not immediately report the discovery to the competent authorities. Even then, in fact, the law established that things found by chance with artistic, historical, archaeological or ethnographic interest belonged to the State. A friend of theirs wrote to the then President Giuseppe Saragat on their behalf to report the find and their intention to offer it as a gift to the President. Obviously Gaetano's family hoped to receive some form of reward, however, having not told the authorities, the fisherman risked being accused of theft. In fact, five days later, the police entered the home of the Graniero family and confiscated the artefact. After months of judicial troubles, the court rejected the accusation of theft because the fisherman had reported the find to the highest office of the state, thus being rewarded with two million lire. Nowadays, thanks to its careful restoration, the "rusty bucket" is considered one of the most beautiful archaeological treasures of late-antique art.

The silver amphora of Baratti – the symbol of a world that does not want to die

Dated the late-4th century AD, the Baratti amphora is a unique artefact with exceptional characteristics: it is made of almost pure silver, weighs 7.5 kilos, is 61 centimetres high, and could contain up to 22 litres, probably wine. The traces of welding on the shoulder and at the base of the neck indicate that it originally had two handles. Although smaller than the Baratti amphora, only two other silver specimens with a similar shape are known: one from Moldova, now kept in St. Petersburg, the other belonging to the "treasure of Sèuso" – similar to products from the eastern Mediterranean, the shape of the vase suggests that it comes from the workshops of Antioch in Syria or from silversmiths' workshops in the Danube area. However, the decoration of the Baratti amphora is much more complex and is unique: 132 clìpei, oval-shaped medallions, cover the surface of the vase showing figures created in relief down to the smallest detail. Even today, thousands of years after its creation, we are able to understand its theme: at the top, on the neck, twelve busts with depictions of the god Mithras and Attis face each other in pairs, divided into two registers, with an allusion to the months or Zodiac signs. Four other pairs of similar busts decorate the base of the neck on a single register and reproduce the rhythms of the seasons. In the central body, seven registers depict a procession in which children play or dance among Maenads, Satyrs and Korybantes. In the centre, a formidable sequence of pagan divinities, including Kronos, Zeus, Cybele, Dionysus, Apollo and Aphrodite, each with their fundamental attributes are clearly recognisable as if they were slides. Below the gods, the Dionysian procession continues and, even further down, there are festive dancers. On the foot of the amphora, there are images recounting the myth of Eros and Psyche. As if it were a film, the figures follow one another in a whirlwind, twirling and celebrating in cheerful, noisy procession. At the time the silver amphora of Baratti was made, the great Roman Empire was going through a period of profound changes. Paganism was slowly becoming more and more of a minority religion, the divinities represented in the amphora being neglected in favour of the new irrepressible religion of the time, Christianity. In 380 AD, the Emperor Theodosius published the Edict of Thessalonica, proclaiming Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, thus implicitly sanctioning the condemnation of paganism. Baratti's silver amphora thus represented a world anchored in the past with a solid point of reference in classical polytheism that did not want to die, but which, was doomed to shipwreck.

The End of the ancient city

In November 415 AD, a few years after the invasion of the Visigoths, the poet Rutilio Namaziano, a Roman aristocrat of Gallic origin travelled by sea from Rome to survey his possessions which had been devastated. He stopped at Baratti and, with the conscious and poignant melancholy of those who witness the collapse of their world and of the values in which they believe, described the ruins of Populonia thus: “It is no longer possible to recognize the monuments of the past era, immense terraces have consumed voracious time. Only traces remain between collapsed buildings, their walls and roofs lying buried in vast ruins. Let us not be indignant that mortal bodies disintegrate: here too cities can die. Despite this, Populonia still maintained its role as an urban centre for some time and, from the late-5th century, it became the seat of the diocese. The events of San Cerbone, Bishop of Populonia, fighting against the Gothic King Totila, mark the last chapter of the ancient city. Shortly afterwards, in order to escape incursions from the sea, the diocese was moved to Massa Marittima, the ancient town of Populonia remaining only in name for a long time. A castle occupying the area of the ancient ruined city was built to guard, the gulf and the port, called Pòrtus Baràtori. Populonia fell into the hands of the Lombards around 580AD, but the lack of documentation and archaeological evidence from this period does not allow us to integrate an already very uncertain historical picture of the area. However, the port must still have been trading: an account from the early 9th century describing how an assault by Saracen pirates was repulsed by about forty defenders. Not long afterwards, under the dominance of Pisa, political and economic control of the region was transferred to Piombino.

The Territory in the Middle Ages

Around the year 1000AD, the Gherardesca counts redeveloped the heart of the Campigliese mining basin and the fortified village of Rocca San Silvestro, which housed the workers who mined and worked the metal that was destined to be sold to the great merchant powers, Lucca and Pisa. The history of the area from the Middle Ages to the present day is presented through illustrative panels, and you can discover the history of this castle by visiting the Archaeological Mines Park of San Silvestro and the small museum where the archaeological materials from the excavations of the village are kept. Thus, the beating heart of the local economy moves from ancient Populonia to Campiglia and Massa Marittima, new centres that sprang up in the hinterland. The Benedictine monastery of San Quirico, which can be visited in the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Populonia, was a site of great importance for the redistribution of settlement structures and the geography of power in this period. Iron production was now managed from Pisa, on behalf of which itinerant blacksmiths operated – groups of specialized workers who moved to where the raw materials were available and produced good quality semi-finished iron on site. With Pisa’s political power crisis at the end of the 13th century, however, the production of iron also declined. In fact, during the following century, there were internal political struggles, a demographic crisis and a deep recession, associated with a slowdown in mining production and economic diversification in this region, where hydrographic instability led to the expansion of forests and marshes.

The modern age and the rediscovery of archaeological heritage

Established in 1399 under the Appianos, the state of Piombino included the seaside town of Piombino, the castles of Populonia, Suvereto, Scarlino, Buriano and the island of Elba. Despite periods of relative political and economic prosperity, the hydrographic changes in the area led to the expansion of forests and marshes, triggering a malaria outbreak that lasted until the early-19th century. Only briefly under the French government of Elisa Bonaparte and Felice Baciocchi, followed by the Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold II (to whom the Principality of Piombino was assigned, following the fall of Napoleon) was the reclamation of these areas tackled – an issue which also affected governmental decision-making from the unification of Italy up to the late-20th century. The 20th century also saw flourishing of new initiatives linked to the development of the iron and steel industry. The recovery of the huge Etruscan iron slag heaps, which still contained a relatively high percentage of ore, began in Baratti. Undertaken on an industrial scale from the end of the First World War to 1959, these massive excavation works brought to light most of the Etruscan monuments that you can see today in the Archaeological Park of Baratti and Populonia. Carried out with the aid of mechanical means, however, the recovery operation also caused irreparable damage to the archaeological heritage. Only the competent surveillance, careful recording of data and incessant activity and dedication of Antonio Minto, who was first an official and then the Superintendent of Etrurian Antiquities, allowed anything to survive. This museum is thus dedicated to him.

The Mascìa collection

Recently restored to the public at the Archaeological Museum of the Piombino Territory, on display in front of you, you can see some of the most beautiful and significant finds from the Mascìa Collection. Like many other local boys, Salvatore Mascìa collected and admired the innumerable shards and small artefacts scattered on Baratti beach. Stimulated by these finds, he became increasingly passionate about our common past and archaeology, investing energy and resources in the purchase of vases, furnishings and other goods in the creation of a significant collection of over 200 pieces. For many years, Mascìa's Florentine residence enjoyed unique and precious furnishings. A privilege reserved for few people, in the space of just a few meters, guests to his home were able to admire thousands of years of human artefacts, including Egyptian statuettes, Etruscan and Greek vases and even bronze bracelets – wondering who could have produced and used those furnishings must have been an amusing pastime for those lucky enough to pass through the front door. Between 2015 and 2016, Mascìa decided to renounce private management and donate 83 specimens from his valuable archaeological collection to the Museum – a heterogeneous set of archaeological finds covering more than 700 years of human history and coming from the richest cities of the ancient Mediterranean basin. In excellent condition and, in many cases, of excellent artistic quality, the pieces donated to the museum highlight not only the skill of the craftsmen, but also the peculiar stylistic characteristics of the civilizations that produced them. The exhibition has been organized into thematic sections: at the top left, you can observe ancient objects used for body care and cosmetics, immediately below which there are pieces depicting animals and monsters such as mermaids and sphinxes. The other showcases contain a great variety of exhibits that were used for the consumption of wine in ancient times. Salvatore Mascìa’s collection of antiquities also includes 5 small Egyptian statuettes, measuring between 9 and 13 cm. Enigmatic human figures, with their hands crossed on their chests, they were found in large numbers inside the tombs of the pharaohs and the richest members of Egyptian society. As we know, the Egyptian conception of the afterlife was based on the belief that, after death, all daily activities continued. Those who could afford it certainly did not want to run the risk of having to perform menial jobs in the afterlife, and thus statuettes of 'substitutes' who were supposed to serve them for eternity in the afterlife were created. It is no coincidence that some specimens from the Mascìa collection display typical working equipment, for example, a hoe and sack.